Often we are unaware of the long and arduous journey food takes before reaching our plate. Retaining food freshness is in part due to creating gaseous micro environments that ensure the preservation of food quality.

In the United States, it is estimated that food typically travels between 1500 and 2500 miles1 between the farms where it is produced and the dinner table where it is ultimately consumed. What we think of as ‘fresh’ fruit and vegetables may also have been in storage or travelling for much longer than we think, potentially up to four weeks in the case of lettuce.2

Even for locally-sourced produce with reduced food miles, it is important for suppliers to ensure the maximum quality and freshness for their produce. This is because without careful storage for transportation, the vitamin content of fresh foods can deteriorate3 as well as the appearance of the produce, making it more difficult to sell to consumers.

One very successful approach to preserving food quality during transportation and storage is the use of gaseous micro environments in food packaging and storage. This is known as modified atmospheric packaging (MAP), or atmospherically modified package (AMP), where the foods are packed in containers with an environment of carefully-controlled gas concentrations.4 A huge number of the foods we buy make use of MAP to enhance their freshness and shelf lives without the need to add preservatives or modify the food itself in any way.

Fresh Micro Environments

Transportation of fruit and vegetables is usually performed under refrigerated conditions, regardless of the means of transport, typically around 5°C with carefully controlled humidity.5 The chilled conditions help to slow the growth of any microorganisms and extent the lifetime of the food, in conjunction with the use of MAP.

Despite the undoubted effectiveness of MAP in preserving produce quality6, optimal gas mixtures for MAP vary from produce to produce. For example, for most plant-based produce, some O2 content in the atmosphere helps the plant to respire, but these need to be balanced with increased CO2 concentrations to slow the rate of respiration sufficiently to increase the produce lifetime.7,8 However, there can be subtle differences between the optimum conditions for different types of fruit and vegetables, such as citric fruits which can only tolerate a lower limit of a 5 % O2 concentration, unlike apples and pears that can cope with O2 concentrations down to 1%.9

Such careful control of the environmental conditions for optimum fruit and vegetable preservation during transportation, relies then on highly-sensitive gas sensors capable of distinguishing the smallest of changes in gas concentration. The typical gases used in MAP for fresh fruit and vegetable preservation are CO2, O2 and sometimes N2.

Sensors for Creating Micro Environments

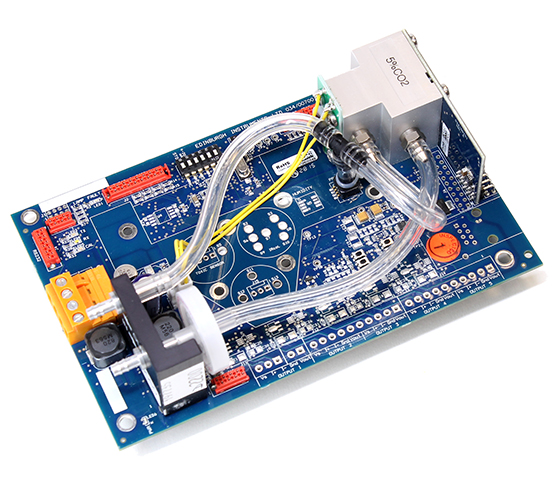

Edinburgh Sensors offers a range of gas monitoring options well-suited to creating micro environments to ensure quality control during fresh food transportation. Their range of CO2 online monitoring sensors includes the Guardian NG, Gascard NG, the IRgaskiT and the Gascheck, will cover most customer needs for food transport applications.

Where low-cost, highly-robust gas monitors are desirable, the Gascheck is an ideal option. Capable of detecting CO2 concentrations in the 0-3000 ppm range, with a zero-stability of ± 3 % over 12-months and an accuracy of ± 3 % over the full detection range. Depending on the particular version of the Gascheck, the response time can be as low as 30 seconds, with an initial warm-up time of 5 minutes.

Where higher accuracy is desirable, the Guardian NG comes in a range of options with an accuracy of ± 2 %. The Guardian NG also has a convenient interface which displays true volume % readout over a wide range of pressures as well as being capable of displaying historical graphical information over a user-defined period. If necessary, there are built-in alarm systems to warn if gas concentrations deviate too much or the possibly to connect and interfacing with external logging devices.

The Gascard NG comes now in two versions, either as the stand-alone card, or as the Boxed Gascard to minimise installation and set-up time. The Gascard is capable of detecting CO2 concentrations in the range of 0 – 5000 ppm and, like the other Edinburgh Sensors products, can also operate in humidity conditions spanning 0 – 95 %. By using RS232 communications the Gascard can be integrated with other control or data logging devices, also with the option for on-board LAN support where required.

Better Produce with Micro Environments

Edinburgh Sensor’s full range of instruments comes with both pre- and post-sales technical support and these devices build on their nearly 40 years of expertise in a range of gas sensor technologies. Most of these products are based upon infra-red detection, which facilitates their very high sensitivities for gases such as CO2 or other hydrocarbon species like methane and in systems like the Boxed Gascard, the infrared source is field-replaceable.

Online monitoring of gas concentrations for MAP applications allows maintenance of optimum conditions for fresh fruit and vegetable preservation, which is highly beneficial not just for ensuring better quality produce, but also ensuring less food spoilage and wastage and the cost-savings associated with this. For more information on our range of sensors for the creation of gaseous micro environments, contact a member of our team at sales@edinst.com.

References

- B. Halweil, Home Grown: The Case for Local Food in a Global Market, World Watch Institute, 2002

- How old are the ‘fresh’ fruit and vegetables we eat, https://bit.ly/2zkPheH, (accessed February 2019)

- M. I. Gil, F. Ferreres and F. A. Tomás-Barberán, J. Agric. Food Chem., 1999, 47, 2213–2217.

- B. Ooraikul, Modified Atmosphere Packaging of Food, Springer, 1991

- Packing Fresh Fruit and Vegetables, https://bit.ly/2Ecqita, (accessed February 2019)

- E. M. Yahia , Modified and Controlled Atmospheres for the Storage, Transportation, and Packaging of Horticultural Commodities, Taylor and Francis Group, USA, 2009

- Modified Atmospheric Packaging Poster, https://bit.ly/2TczaII, (accessed February 2019)

- S. Mangaraj and T. K. Goswami, Fresh Prod., 2009, 3, 1–33.

- A. A. Kader, D. Zagory and E. L. Kerbel, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 1989, 28, 1–28.